Exploring FP-TS through the Composition

Suppose you have checked the documentation of fp-ts. In that case, you will find that there are dozens of modules, many of them with dozens of functions, and most of them are undocumented, only signature, so getting started with fp-ts will be steep for a beginner if you don’t have much functional programming experience.

Why composition way?

This got me thinking that there should be an easier way to learn from such a popular library, and after watching a few talks and reading a few books, I found the answer.

After you read this article, it will make your life easier too!

What are the core principles of Functional Programming?

Before jumping into the fp-ts, I’d like to ask you a question first: What are the pillars of functional programming? Or, to put it another way, what do you think are the core principles of functional programming?

If you ask chatGPT this question, it will answer you Functions are first-class citizens, Immutability, Higher-order functions, etc. These things are fundamental and not essential enough; I say not essential enough because even if we know them, we still can’t write easy-to-change code based on them.

So I prefer the definitions of Scott Wlaschin and the author of fp-ts: Gcanti, where Scott says the core principles of functional programming are

- Functions are things

- Composition everywhere

- Types are not classes

Gcanti mentioned similar things in his book.

The two pillars of functional programming

Functional programming is based on the following two pillars:

- Referential transparency

- Composition (as universal design pattern) All of the remaining content derives directly or indirectly from those two points.

They all discussed “composition” in depth in their books or talks, which shows the importance of composition.

Composition of normal functions

When you are writing some happy path functions, you are combining normal functions, so let’s look at some simple Js code.

function add1(x) {

return x + 1;

}

function double(x) {

return x * 2;

}

function square(x) {

return x * x;

}

// normal composition

const added1 = add1(2);

const added1AndDoubled = double(added1);

const squared = square(added1AndDoubled);

added1AndDoubled // 6

If we don’t want to have so many variables, then we can write a compose function.

This is a higher-order function that takes two functions as arguments, returns a function that takes x, and returns the result of g and f operations on x.

const compose2 = (f, g) => x => f(g(x));

const add1AndDouble = compose2(double, add1);

add1AndDouble(2) // 6

Of course, we could also write a generic one with more than two parameters.

// compose

function compose(...fns) {

return fns.reduce((f, g) => (...args) => f(g(...args)));

}

compose(square, double, add1)(2); // 36

// 2 |> add1 |> double |> square // 36

In fp-ts, there is a more general, secure, and flexible implementation.

import { flow, pipe } from "fp-ts/function";

const add1 = (x: number) => x + 1;

const double = (x: number) => x * 2;

const square = (x: number) => x * x;

// flow is the reversed version of compose

const f = flow(add1, double, square);

f(2); // 36

// pipe is the same as |> in F#, Elixir, OCaml, and so on

// 2 |> add1 |> double |> square // 36

pipe(2, add1, double, square); // 36

Compose an effect function with a normal function

Well, that’s the first way to compose. Next, let’s look at the second one, the second one is about the effect.

Side effect

We like pure functions, but we work with effects almost daily, so what is an effect?

To understand this, we have to know what the side effect is first. Check out the following function.

const inverse = (n: number): number => {

if (n === 0) throw new Error("cannot divide by zero");

return 1 / n;

};

const x = inverse(0) + 1;

As I understand it, a side effect is an unexpected output plus the original output. We usually use exception in imperative programming and OOP to handle side effects.

Benefits and drawbacks of exception

Benefit

It allows us to focus on the happy path, simple, we just need to throw an error and try-catch to catch it later.

Drawbacks:

The first drawback is that it is hard to find the right place to put try-catch, and it’s too easy to forget one, and before you know it, your application crashes.

Another drawback is the exception way will make our code impure, we all know that the biggest benefit of type programming is that the code becomes easy to reason with the help of the compiler, we can hover types to see the input and output with the help of the editor, this is what is often called referential transparency in functional programming, and exception breaks all that, you can’t model an exception by type. So the signature will lie to you, like our inverse function above, it tells you it expects a number and returns a number, but it actually has other outputs

Either

So is there a better option? My answer is yes. This is Either

The type definition of Either is as follows.

interface Left<E> {

readonly _tag: "Left";

readonly left: E;

}

// represents a success

interface Right<A> {

readonly _tag: "Right";

readonly right: A;

}

type Either<E, A> = Left<E> | Right<A>;

This structure is wonderful, isn’t it? And if you write Elixir a lot, you’ll see that it’s very similar to the structure of {:ok, result} | {:error, error}.

In the world of fp, is this effect? Surprisingly, fp has a broader definition of an effect than you might expect, and Either is just one of them. Another common effect is Option<>

type None = {

readonly _tag: "None";

};

type Some<A> = {

readonly _tag: "Some";

readonly value: A;

};

type Option<A> = None | Some<A>;

What is an effect?

- A generic type:

Array<>- A type enhance with extra data:

Option<>,Either- A type that can change the outside world:

Task<>,TaskEither<>- A type that carries state:

State<>

— steal from Scott’s talk: The Functional Toolkit

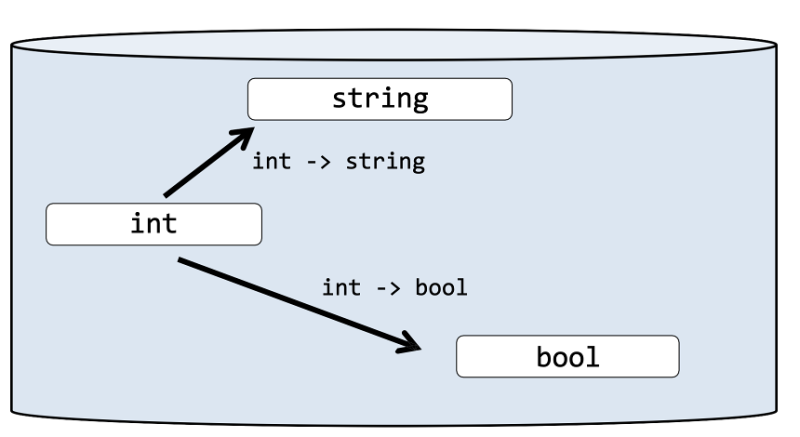

In Scott’s words, the effect can be anything ambiguous, so let’s imagine an effect world. Ok, Since there is an effect world, what is the normal world?

In the Normal world, In fact, you have some common types that can then be converted to each other.

Normal world vs effect world

Normal World

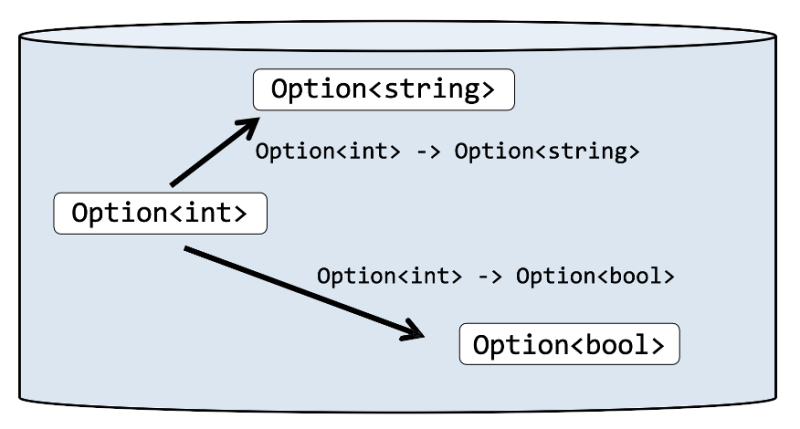

Option World

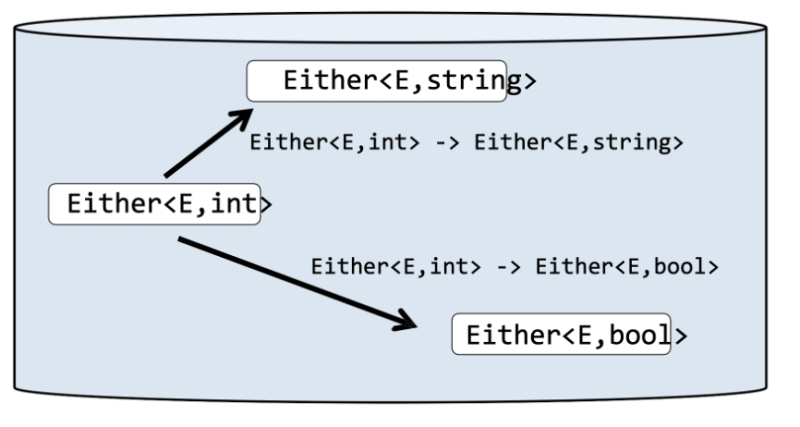

Either World

— steal from Scott’s talk: The Functional Toolkit

You may find the word effect a bit confusing, I have also had, and then I found the answer in this article, the author’s suggestion is to distinguish it from side effects and instead consider it as main effect. i.e, i.e, the main purpose of each effect type. An effect is what the type handles.

- Option models the effect of optionality

- Task models latency as an effect

- Either abstract the effect of failures (manages exceptions as effects)

Compose an effect function with a normal function

So the question arises, how should we compose effect with a normal function? Because many times we are concerned about a happy path and some operations are totally pure functions.

Suppose we have a scenario where we need to update the user name and email, then the steps will be:

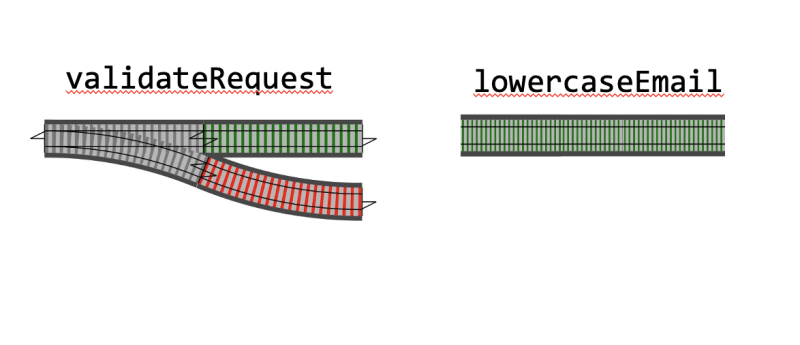

request |> validateRequest |> lowercaseEmail |> updateDb

We can define the type simply as follows

import * as E from "fp-ts/lib/Either";

type Request = {

name: string;

email: string;

};

type ValidationError = string;

// one track input, two tracks output

type ValidateRequest = (request: Request) => E.Either<ValidationError, Request>;

// one track input, one track output

type LowerCaseRequestEmail = (request: Request) => Request;

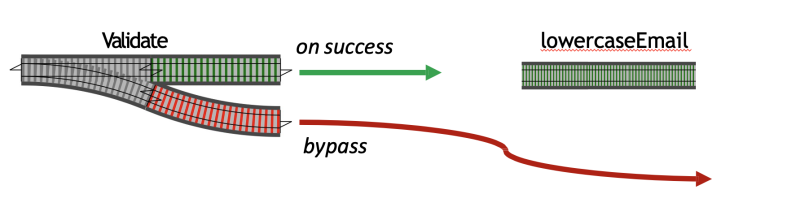

Looking at the definition above we see that validateRequest is a two-track output function, while lowercaseEmail is a pure function that only executes on success and should bypass directly on failure, returning an error.

This means we need to make the above form like this.

So we need a function that: On success, then do something, and on an error, then bypass.

// Answer

import { pipe } from "fp-ts/function";

const validateRequest: ValidateRequest = (request) => {

return request.email.includes("@") ? E.right(request) : E.left("invalid email");

};

const lowerCaseRequestEmail: LowerCaseRequestEmail = (request) => ({

name: request.name,

email: request.email.toLowerCase(),

});

const request: Request = { name: "scott", email: "Scott@example.com" };

pipe(request, validateRequest, E.map(lowerCaseRequestEmail)); // ? E.right({ name: 'scott', email: 'scott@email.com' })

With the map function, we can convert a single-track input and output function into a two-track input and output function. The definition of Either.ts is quite simple.

// transforms functions `B -> C` to functions `Either<B> -> Either<C>`

const map = <B, C, Err>(g: (b: B) => C): ((fb: E.Either<Err, B>) => E.Either<Err, C>) =>

E.match(

(err) => E.left(err), // bypass

(b) => {

const c = g(b); // do the lowercase

return E.right(c);

}

);

As you can see from the definition, this map/1 implements the transformation we described, which lifts a normal world function to the effect world, then this function can take effect world type and return effect world types, Remember this, you’ll see it many times.

Let’s look at another example of the Option.ts, which we have just seen its definition.

When our input may be none, we can use fromNullable to construct an Option

import * as O from "fp-ts/lib/Option";

// type Option = None | Some<number>

const double = (x: number): number => x * 2;

const square = (x: number): number => x * x;

const two: number | undefined | null = 2;

pipe(O.fromNullable(two), O.map(double), O.map(square)); //? { _tag: 'Some', value: 16 }

const none: number | undefined | null = null;

pipe(O.fromNullable(none), O.map(double), O.map(square)); //? { _tag: 'None'}

As you can see from this example, when we use O.map to wrap double and square, the entire workflow is executed only when there is a value and returns none if there is none, which is almost the same pattern as we saw the map of Either.ts。

Functor

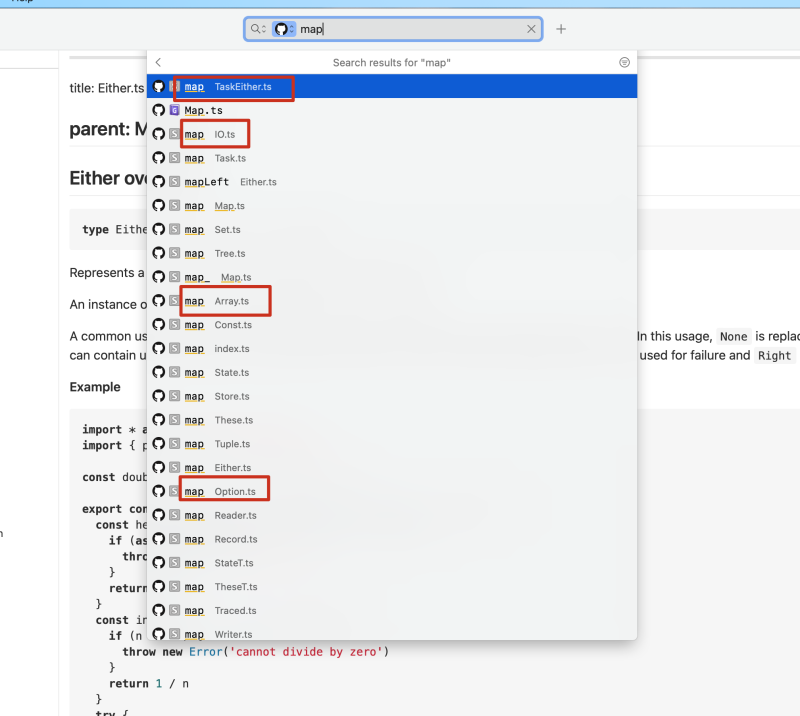

If you search the fp-ts documentation, you will find that almost every module implements a map/1 function.

Because they are both similar from a category theory point of view, they are both functors.

A functor is:

- An effect type:

Either<>, Option<>, Task<>, TaskEither<>, Array<>- Plus a “map” function that “lifts” a function to the effects world, its signature just like this:

map: <A, B>(f: (a: A) => B) => ((fa: F<A>) => F<B>).And it must have a sensible implementation, like the Functor laws

—steal this definition from Gcanti’s book

Compose effectful function with the n-ary function

We have already discussed two compositions, but these two have one thing in common: the output of the first function is the latter’s input.

// composition 1

pipe(n, double, square);

// -> number -> number -> number

// composition 2

pipe(O.fromNullable(none), O.map(double), O.map(square));

// -> Option -> Option -> Option

But things can’t always be so rosy. Suppose we have a function that is multi-parameters. How do we compose an effect function with this multi-parameters function?

const add = (a: number, b: number): number => a + b;

The answer is ap, which, as the name implies, means to apply a function to a value.

Of course, before we learn about ap, we need to know what curry is.

The concept is simple: You can call a function with fewer arguments than it expects. It returns a function that takes the remaining arguments.

// curried version of add

const add = (a: number) => (b: number) => a + b;

const increment = add(1);

increment(1); // ? -> 2

import { ap } from "fp-ts/lib/Identity";

const normalWorldWithAp = pipe(1, add, ap(1));

// -> add1 function -> number -> number

const effectWorldWithAp = pipe(O.some(1), O.map(add), O.ap(O.some(1))); //? { _tag: 'Some', value: 2 }

Based on this, we can quickly write a generic function, let’s call it liftA2

const liftA2 =

<B, C, D>(g: (b: B) => (c: C) => D) =>

(fb: O.Option<B>) =>

(fc: O.Option<C>): O.Option<D> =>

pipe(fb, O.map(g), O.ap(fc));

By checking the type signature, we can find that this liftA2 first receives a curried normal world function, then returns a function that accepts two Options, and finally returns Option.

With liftA2, we can easily derive liftA3 and liftA4 and so on.

Composition of effectful functions

Well, we have already talked about three ways to combine functions, and we still have the last one left, So how to compose two effect functions.

Let’s go back to the validateRequest example we just mentioned, and we are still missing a piece of the puzzle, which is to combine updateDB with the original logic we wrote. Let’s start by simply defining updateDB. For simplicity, my ValidationError is equivalent to a string.

const updateDB = (request: Request): E.Either<ValidationError, Request> => {

if (request.name === "scott") {

return E.left("scott is not allowed");

}

return E.right(request);

};

If we compose them using E.map, then the result will give us a nested Either, but what we want is the Either inside.

// client

const request: Request = { name: "scott", email: "Scott@example.com" };

const result = pipe(

request,

validateRequest,

E.map(lowerCaseRequestEmail),

E.map(updateDB)

);

result; //?

// Either<ValidationError, Either<ValidationError, Request>>

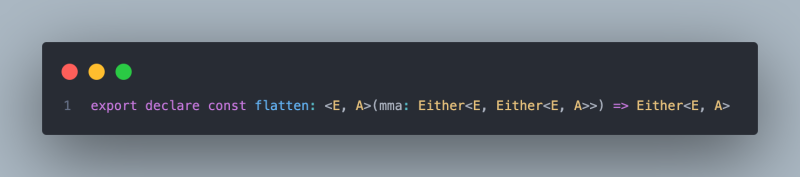

So how do we do it? Yes, we need E.flatten

Its signature looks like this.

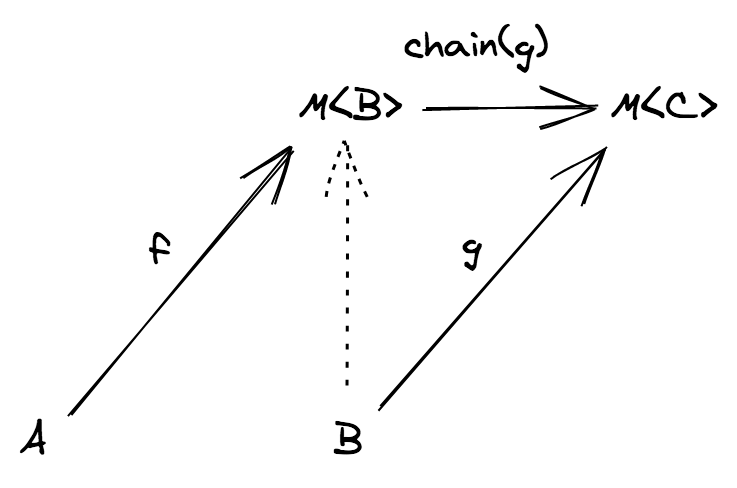

This pattern of flatMap is so common that we have a function to do this, which is chain

chain = flatten ∘ map(g)

Yes, this is the monad.

Definition. Three things define a monad:

- a type constructor M admitting a functor instance

- a function of (also called pure or return) with the following signature: of:

<A>(a: A) => M<A>- a chain function (also called flatMap or bind) with the following signature: chain:

<A, B>(f: (a: A) => M<B>) => (ma: M<A>) => M<B>The of and chain functions need to obey three laws: …

I will not expand on the definitions here because some resources are better than what I’m talking about.

Conclusion

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure (unary) | map(g) ∘ f |

| effectful | pure, n-ary |

liftAn(g) ∘ f |

| effectful | effectful | chain(g) ∘ f |

We have talked about four combinations in total. The first one, pipe or flow, is the most used, while the third one, liftAn, is relatively less used because often liftAn may not be as clear as a closure function, But it is worth learning it because some common tools like sequence vs sequenceT - fp-ts-contrib are based on it.

These four combinations cover at least 90% of our daily work, and the biggest benefit is that it allows us to organize our code more simply, and to let it fit our brains.

References

- https://www.slideshare.net/ScottWlaschin/the-power-of-composition

- enricopolanski/functional-programming: Introduction to Functional Programming using TypeScript and fp-ts. https://github.com/enricopolanski/functional-programming

- Practical Guide to Fp-ts P5: Apply, Sequences, and Traversals

- Why the free Monad isn’t free - by Kelley Robinson - YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0lK0hnbc4U&ab_channel=ScalaDaysConferences